Understanding zippers

A zipper is a cool concept for immutable data types. You don’t have a zipper by itself; instead, you can “zipperfy” other data structures. For example, you can have a list zipper, tree zipper, graph zipper, and so on. A zipper lets you keep a focus point on the underlying data structure, making operations around that focus point more efficient.

To get why zippers are useful, let’s first understand the problem they solve. So, before diving into what a zipper is, let’s talk about updating immutable data.

“Update” for Immutable Data Types

One big issue with many immutable types is that their update operations can be pretty slow. For example, updating a compact array with an index is O(1) because the index acts like a “cursor,” letting you directly access the data you want to change. Once you find that data, you can update it in place. But with an immutable array, updating is O(n) because you need to create a new array and copy all the elements, even though most of them stay the same. Since we’re dealing with immutability, destructive updates are a no-go. If we want to update anything, we need to rebuild the whole structure. The good news is that, because the data is immutable, we can share as much data as possible between the old and new structures.

The cost of updating a value is the cost of traversing the structure to find that value, plus the cost of building the new structure with the new value, while keeping the most shared data. For example, to update an immutable array, first we need to traverse the array to find the value to update, which is O(n). Then, with sharing, we need to build a new array from the that value to the end of the original array. Let’s say the cost for rebuilding is O(k), then the total cost is O(O(n) + O(k)), which is O(n).

An interesting phenomenon is that the cost of traversing is usually less than or equal to the cost of rebuilding. So so when thinking about the overall cost usually you can just think about the the cost of construction. For example, an immutable hashmap is usually implemented as HAMT (hash array mapped trie). It’s a tree but support O(1) lookup. The cost of rebuilding the tree from root to child O(logn), thus the overall complexity is O(logn).

Let’s take a close look at immutable tree:

data Tree k v = Node (k, v) [Tree (k, v)] | Leaf (k, v) deriving (Show, Eq)

tree1 =

Node ("A", "A")

[ Node ("C", "C")

[ Leaf ("E", "E")

, Leaf ("D", "D")

, Leaf ("F", "F")

]

, Leaf ("B", "B")

]

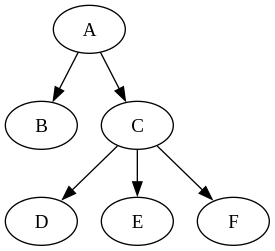

Say we want to update E to E'. Let’s assume we have a function update :: k -> (v -> v) -> Tree k v -> Tree k v for this. The process would be: first, find E; then, create a new node E'. Since E is connected to C, we need a new C' that points to E', D, and F, just like C does. Then, we have A, and we do the same thing for A. By doing this, we only need to create A', C', and E', which is just the height of the tree. The cost of finding E is O(logn), and the cost of building the new tree from E back up is also O(logn), so we can simply say the complexity is O(log n).

update :: k -> (v -> v) -> Tree k v -> Tree k v

update a f (Leaf (k, v)) = Leaf (k, if a == k then f v else v)

update a f (Node (k, v) children) =

Node (k, if a == k then f v else v) (fmap (update a f) children)

If the tree is tall, this is still pretty costly. If the tree is unbalanced, it can get to the worst case of O(n).

Even though we call it an “update,” what’s actually happening is that we’re transforming the old tree into a new one. The end result is similar to an in-place update, but the meaning is different.

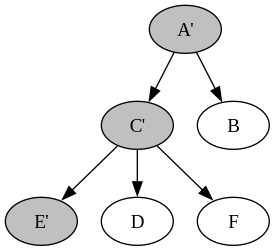

What we’ve talked about so far is just a single update operation. But often, you’ll want to do multiple updates around a certain node. For example, if the tree represents GUI elements, you might want to change the color of all siblings of E to red. The update would look like this:

updateChain = update "E" (const "E'")

. update "D" (const "D'")

. update "F" (const "F'")

tree2 = updateChain tree1

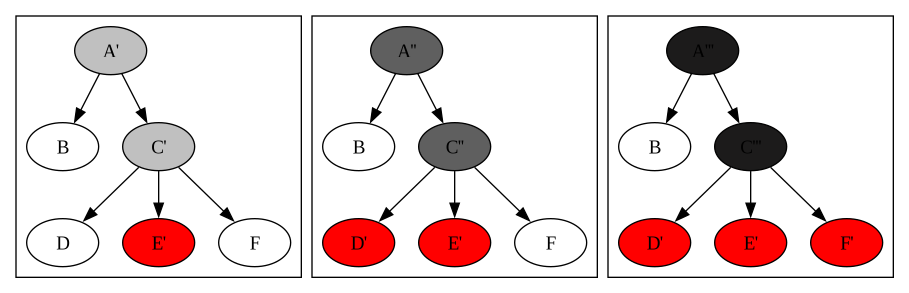

See? A and C are not changed, but because we are composing update, we need to copy them over and over again. Every time we invoke update, we need to update both A and C. Since we called update three times, this operation will need to be performed three times because every update starts from A. Imagine doing this to a DOM tree in the browser with thousands of nodes; a lot of unnecessary actions will be performed.

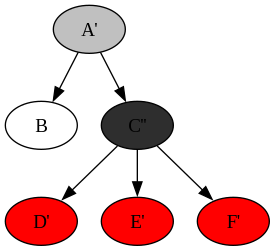

A simple way to mitigate this is to only call update on the subtree C, then attach the updated subtree C'' back to the original tree. We still need to update C three times, but A is only updated once.

updateC :: Tree a -> Tree a

updateC (Node kv children) = Node kv (fmap go children)

where

go ctree@(Node ("C", _) _) = updateChain ctree

go other = updateC other

updateC _ l@(Leaf _) = l

By calling update closer to where the update should happen, we avoid unnecessary copies along the search path from A to C. C is the focus point; to update all children of C, we only need to map update to all of them. The problem with this approach is that it’s an ad hoc solution, it’s not composable, and you need to know the specific structure of the tree. It would be great if we could set a focus point of the tree so that every time we want to perform some action around that focus point we don’t have to go through the path from the root again. This is where zippers can help.

Tree Zipper

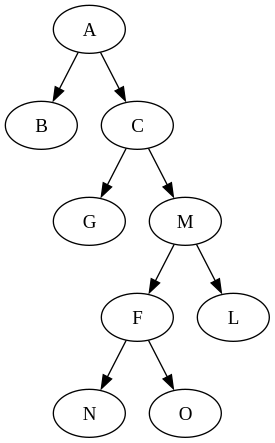

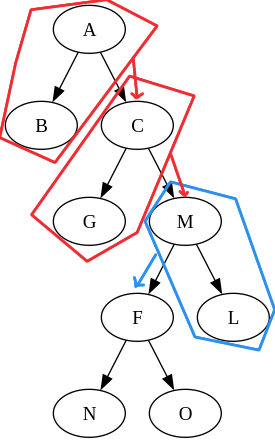

Take a look at the following binary tree:

Let’s say we want to update L and M. Based on the conclusion we made above, we want to perform the update around F instead of the root to avoid unnecessary copies. So, we want F to be the focus of our tree. We need a structure that lets us call update from F as if F is a standalone subtree, then automatically stitches the updated subtree F' back to the original tree.

Luckily, we already have something that does this: the tree zipper! The zipper of the original tree looks like this (Note: this isn’t the exact code representation, it’s just to help visualize):

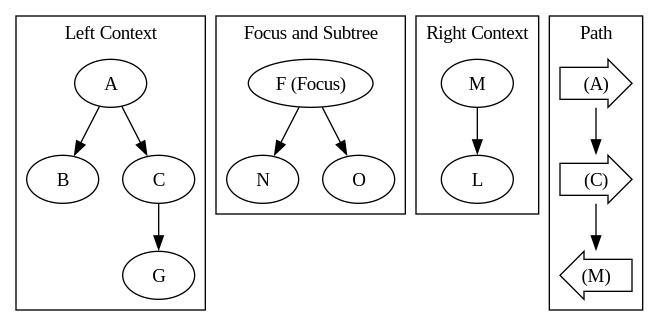

This graph looks nothing like the original tree, but trust me, it holds the same amount of information and more. We split the tree into three components: the left context, the focus, and the right context. The focus is the subtree of F that we want to operate on. The left and right contexts are the parts of the tree surrounding the focus. Additionally, we maintain the extra path information that records the path from the root to the current focus.

Left and right contexts are obtained by the process of “zipping.” The process goes as follows: First, we find the path from the root A to F as A -> C -> M -> F. For A -> C, we need to go to the right of the tree, so we put A and its left subtree into the left context. Then we descend from C -> M, which is also going right, so C is added to the left context. For C -> M, we go to the left, so we put M and its subtree into the right context. Finally, when we find F, we take it and its whole subtree as the focus. Pay attention to the path; it’s crucial to maintain the original structure of the tree.

How do we restore the original tree from this? First, we bring back the right context. Because the last step of the path is (right, M), we know M is to the right of the focus. We pop the path (right, M) and attach the focus as the left child of M. The result is this partially restored tree:

We keep popping the path. The next path is (left, C), so we add the subtree M as the right child of C. Because C and A are both in the left context, at this point, we’ve already reconstructed the original tree. This proves that the zipper representation holds the same information as the original.

The interesting part of this structure is that the focus is stored as a standalone tree. So, to update the children of F, we don’t need to start from A; all we need to do is update the F subtree. Because the focus is stored separately, we don’t even need to reconnect it back to the tree. All updates are local and minimal.

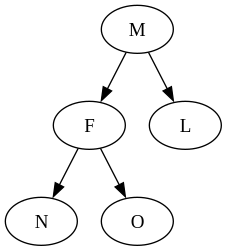

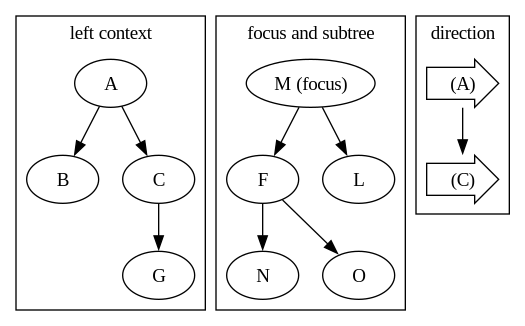

We can also easily shift the focus. If we want to work around the node M instead of F, we can do this: pop the (right, M) path, so we move up right to M. We add the F subtree as the left child of M and make the entire M subtree the focus. Because M is the root of the right context, after moving it to the focus, there’s nothing left in the right. The zipper with the new focus looks like this:

You can try to restore the tree yourself to prove it’s still the same tree. But now, we can work around M much more efficiently. For example, if we want to update F and L in one go, the only overhead is copying M. Moreover, we can keep moving the focus anywhere we want in the tree and always keep the update local. Though the complexity is still log(n), it’s doing far less repeated work compared to the vanilla tree.

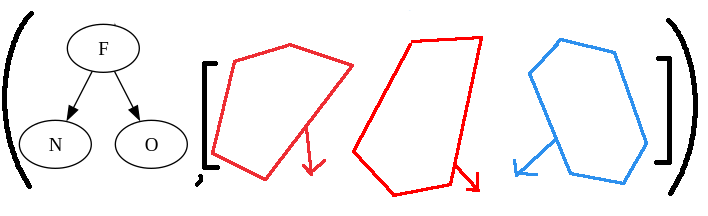

One observation is that with any focus in the tree, it’s either directly connected with its left context or right context. For example, F is directly connected to its right context M, and M itself is directly connected to its left context C, which connects to its left context A. It’s a recursive process. This means as we walk down the tree, the context is added incrementally. Let’s define the zipper as a tuple (Focus, [TreeDirection]) where Focus is the current focus, and TreeDirection is the direction of the context tree relative to the focus plus the context tree itself. If we think about focus this way, the path from A to F looks like this:

When the focus is on A, we don’t have any context because the focus is the entire tree. Once we walk to C, the subtree of C becomes the focus, and the tree A -> B becomes the first left context. Then we move right to M, which adds C -> G as its direct context. This goes on until the focus reaches the target node. The final zipper looks like the following tuple:

If we combine all the left contexts into one big left context and all the right contexts into one big right context, we can get back to the earlier graph that split the tree into three components. This representation still ensures that the focus is a standalone tree, which means we can work with it efficiently. In addition that, it also preserves the history of the path and the context from the root to the focus. It’s compact and cleanly defined.

Now we can start converting it into code.

data BinaryTree a = Leaf a

| Branch a (BinaryTree a) (BinaryTree a)

deriving (Eq, Show, Ord)

data TreeDirection a = TreeLeft a (BinaryTree a)

| TreeRight a (BinaryTree a)

deriving (Eq, Show)

type Context a = [TreeDirection a]

data TreeZipper a = TreeZipper (BinaryTree a) (Context a)We can create a zipper from a binary tree. To do that, we simply create a Zipper with an empty context.

fromTree :: BinaryTree a -> TreeZipper a

fromTree t = TreeZipper t []We can freely move the focus around the tree.

moveLeft :: TreeZipper a -> TreeZipper a

moveLeft (TreeZipper (Branch x l r) bs) = TreeZipper l (TreeLeft x r : bs)

moveLeft (TreeZipper (Leaf x) _) = Leaf x

moveRight :: TreeZipper a -> TreeZipper a

moveRight (TreeZipper (Branch x l r) bs) = TreeZipper r (TreeRight x l : bs)

moveRight (TreeZipper Leaf x) = Leaf x

moveUp :: TreeZipper a -> TreeZipper a

moveUp (TreeZipper t ((TreeLeft x l) : bs)) = TreeZipper (Branch x l t) bs

moveUp (TreeZipper t []) = tOf course, we can modify the focus, which is why we’re here in the first place.

modify :: (a -> a) -> TreeZipper a -> TreeZipper a

modify f (TreeZipper (Branch x l r) bs) = TreeZipper (Branch (f x) l r) bs

modify _ (TreeZipper Leaf bs) = TreeZipper Leaf bs

set :: a -> TreeZipper a -> TreeZipper a

set a = modify (const a)Note that we use a binary tree here, but this approach can be generalized to any trees or even graphs.

Conclusion

So, what’s the benefit of a zipper? We get direct focus on the node we want to work around as if we hold a pointer to it, and we have more efficient update operations compared to the default immutable tree. With all these perks, we still preserve everything that the immutable tree gives us. The complexity of other operations like lookup is not affected by the zipper structure, so it’s just a better tree overall. Of course, nothing is free in this world. You do get some additional complexity with the zipper. Instead of just thinking about the tree as nodes and edges, you need to think about the context and focus as well. This extra complexity may or may not be worth it depending on the use case. If you don’t need to frequently update, or the tree is short enough, you may get no benefit from doing all this extra hassle.